If greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced by at least 90% by the middle of the century, the survival of civilization will depend on high technology and shelter cities. However, a reduction of 90% can only be achieved if no more fossil carbon is extracted and burned. There is no way around the fact that trade in fossil carbon (i.e., crude oil, natural gas, lignite, hard coal, and peat) must be legally restricted and ultimately banned. However, carbon itself is indispensable. Carbon-based materials are and will always remain the core element of the global economy. In the future, however, carbon will no longer be extracted from deposits deep underground but will be harvested from the air and the oceans.

Everyday objects and building materials, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, textiles, food, and much more - no area of life can do without carbon-based materials. The adoption of a gradual ban on fossil carbon will lead to a simultaneous increase in demand for alternative carbon sources and, thus, to an increase in their value. In the long term, there are five principal sources of non-fossil carbon available to us:

(1) Organic carbon from biomass,

(2) CO2 from combustion processes (especially waste incineration and pyrolysis gases),

(3) CO2 from the production of cement or quicklime,

(4) CO2 removal from the atmosphere, and

(5) CO2 removal from the oceans.

Limits of carbon extraction from biomass

The production of organic carbon from biomass is competing with crop production and the protection of ecosystems. Taking into account food security and biodiversity, the global biomass potential for meeting the demand for industrial carbon is about 10 Gt CO2e per year, which is about 20 - 30% of the expected demand for climate-neutral carbon for materials, fuels, and carbon sinks. New biomass strategies such as the cultivation of seaweed and algae, the expansion of plantations of fast-growing biomasses such as bamboo or elephant grass, indoor farming, or the consistent use of cover crops and agroforestry could further increase the available biomass potential. Nevertheless, scaling remains limited by several planetary boundaries, mainly due to land use change, biodiversity loss, groundwater depletion, and over-fertilization. In order to preserve global biodiversity and natural resources, land used for agricultural and industrial forestry should not be expanded but rather reduced in favor of nature conservation areas (see the UN initiative Nature Pledge und Nature Needs Half).

In order to utilize carbon from biomass as efficiently as possible, processing must achieve high rates of carbon retention. When wood is used directly for construction or furniture, when straw chaff is used directly as an additive to clay bricks or when lignin is extracted for the plastics industry and cellulose is used to make composite materials (see carbon sink products, among others), 80 to 95% of the carbon absorbed by plants is retained for the lifetime of the products and can usually be recycled at the end of the product cycle. If the biomass is pyrolyzed into biochar, more than 50% of the carbon is lost in current processes, but a particularly durable form of carbon and usable thermal and electrical energy is produced. If pyrolysis is combined with a process for capturing CO2 from the exhaust gases, the carbon efficiency can even be increased to 80 - 95% (see: Pyrogenic Carbon Capture and Storage).

Even if significantly more biomass were cultivated for carbon utilization and the efficiency of carbon utilization from biomass were increased through material application and CO2 capture, the global amount of available biomass carbon would not be sufficient to completely replace fossil carbon in material application, generate heat, and establish geological sinks. The gap between the amount of carbon required by industry and the amount theoretically available from biomass must be made up by technically removing CO2 from the atmosphere and the oceans. The technologies used for this are known as Direct Air Capture (DAC) and Direct Ocean Capture (DOC).

The CO2 in the atmosphere and the CO2 contained in the oceans are in balance and equilibrate each other with a certain time lag. If a lot of CO2 is emitted, the CO2 in the oceans also increases. If a lot of CO2 is removed from the atmosphere by forests or DAC/DOC, CO2 flows back into the atmosphere from the oceans to maintain the balance. Therefore, the build-up of C sinks also leads to CO2 returning from the oceans into the atmosphere; this process is called reflux.

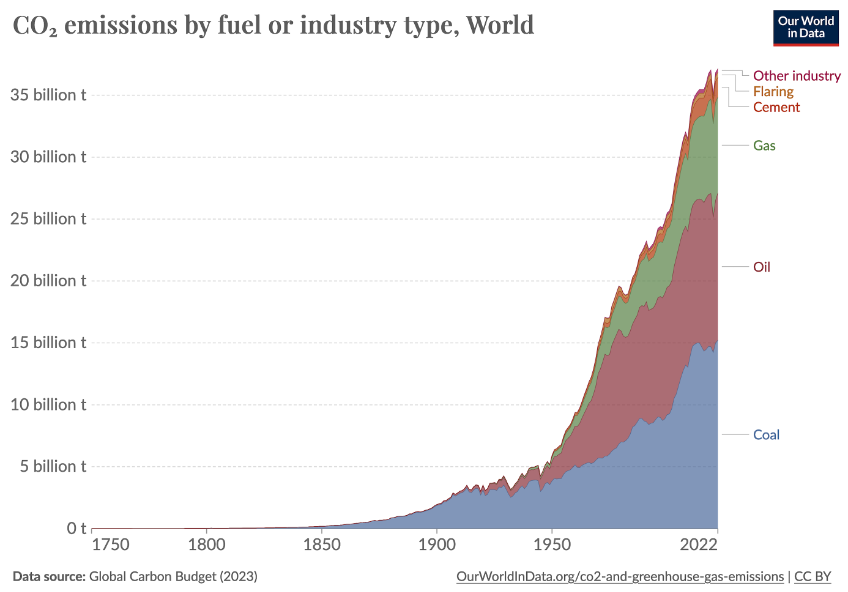

Nearly all fossil carbon emitted over the last 250 years can still be found in the atmosphere, the oceans, biomass, and soils. Using emerging technologies, what was once mined as lignite or extracted as crude oil and natural gas can now be harvested from the air and oceans. Since 1750, the dawn of industrialization, mankind has emitted roughly 1500 Gt of CO2 from fossil sources (link to statista.com). All this CO2 represents an almost unlimited reservoir of carbon that can be garnered for use in industrial applications or as geological C sinks.

Figure 1: Global CO2 emissions since 1750 (https://www.statista.com/statistics/1007454/cumulative-co2-emissions-worldwide-by-country/).

Over the next two decades, the air and oceans will become the most important source of carbon for industrial applications. A new carbon age is beginning, with the out-phasing of fossil carbon while the use of recaptured and recycled carbon soars. As soon as the industry can cost-effectively switch to non-fossil carbon sources, there will no longer be a shortage of carbon. From then on, carbon will be recycled, and it will no longer harm the climate or the environment.

C-sinks from biomass or directly from the air and oceans?

Although the agricultural and marine production of organic carbon in the form of plants and algae can be cost-effective, it is very land-intensive. The resulting carbon is highly chemically complex and presents low entropy, which is wasted when only the basic carbon, not the complex biomaterial, is used for further processes. Processing biomass carbon into standardized chemical compounds requires complex and, therefore, cost-intensive process steps. DAC and DOC, i.e., the removal of CO2 from the air and oceans, require high investment costs, but they are much less land-intensive and can be easily synthesized into the chemical raw material CH4.

With today's technology, DAC is already around 25 times more area-efficient than local forests and 10 times more area-efficient than tropical forests. While 1 hectare of forest in Northern America can absorb around 20 tons of CO2 per year, DAC can remove 500 tons of CO2 from the atmosphere in the same area. This includes the area required to install the solar panels needed to generate electricity and synthesize methane, with methane being the raw product of the chemical and fuel industry. It is to be expected that carbon from DAC and DOC can be provided more cost-effectively than from biomass in the medium term. The capture of CO2 from concentrated waste gases, for example, from waste incineration or cement production, is even more cost-effective.

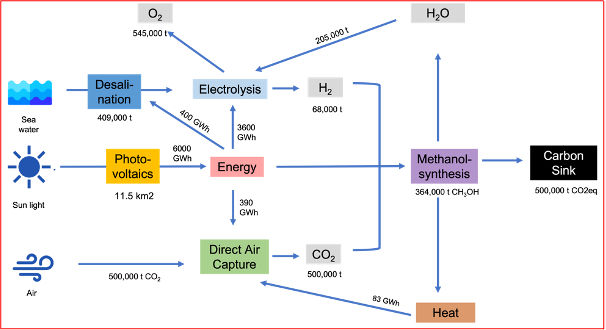

Figure 2: Example of the production of a methanol-based C-sink of 500,000 tons of CO2e. An area of around 14 km2 is required for solar panels, seawater desalination, CO2 capture from the atmosphere and synthesizing CO2 and H2 into methanol.

To remove 10 Gt of CO2 from the atmosphere annually with today's technology and process it into synthetic methane using electrolytically produced hydrogen from desalinated seawater and pyrolyze the methane into carbon black (i.e., artificial biochar) and fix it geologically, only 20% of the land surface of Saudi Arabia or 450,000 km2 is needed to avert the climate crises. This corresponds to 0.3 % of the global land area. To produce electricity worldwide with solar panels, convert it into hydrogen from desalinated seawater, and transport it to every corner of the globe, another 350,000 km2 is needed. Of course, not all of this should occur in Saudi Arabia, but it could be widely distributed across the world, which massively reduces transportation costs and provides enhanced energy and resource self-sufficiency and resilience. It would take less than 1% of the world's land area to supply the entire world with electricity, fuel, heat, chemicals, plastics, fertilizers, and carbon sinks using solar energy. The sun is a reactor that provides free energy every day. Despite this, humanity is in danger of extinction because it is not effectively managing solar energy. [We will publish the specific figures, models, and calculations on which this scenario is based in the next tBJ article.]

Figure 3: Model of a plant that uses solar energy to extract CO2 from the atmosphere and to synthesize methane using hydrogen obtained electrolytically from desalinated seawater. Methane is the main raw material of the chemical industry as well as the starting material for other fuels and artificial biochar. Concept and design by Obrist AG.

Geological and temporary C-sinks

Persistence, i.e., the durability of carbon storage, is a decisive criterion in the evaluation of a carbon sink. A distinction is made between geological sinks, in which the carbon remains largely stable for over 1000 years, and temporary C sinks. Temporary C sinks have a lifespan of at least one to several hundred years. Unlike geological sinks, the C in temporary C sinks is not stored as a persistent biochar fraction in soils or as carbonate in rocks, but in consumer and raw materials or in living biomass such as trees. The preservation of temporary C-sinks (e.g., the existence of a wooden house or the lifespan of a sewage pipe) must be monitored regularly. The carbon stored in temporary C-sinks can decrease or increase steadily, exponentially, or even abruptly (e.g., in forest fires). It is, therefore, crucial that certificates of temporary C-sinks are only issued for the years in which the existence and quantity of the C-sink have been monitored (ex-post) and not for many years in advance (ex-ante).

Given their permanent storage, geological C sinks can offset CO2 emissions and, thus, virtually cancel out their total global warming effect. Temporary C-sinks, on the other hand, cannot be used to offset CO2 emissions once and forever. During their verified lifetime, temporary carbon sinks compensate for the climate impact of a greenhouse gas emission of the same size. If, for example, a temporary C-sink of 100 tons of CO2e persists for 30 years, it can compensate for the global warming effect of 100 tons of CO2e for these same 30 years. After these 30 years, a new 100-ton C-sink must be created to continue compensating for the global warming effect of the 100-ton CO2 emissions.

For the period of the certified existence of a temporary C sink, its climate impact is the same as the climate impact of a geological C sink of the same size.

Competition between C-sink materials and geological C-sinks

The industrial use of non-fossil carbon, whether in the form of biochar, wood, lignin, or synthetic methane, can lead to temporary storage in products such as plastics, composite materials, asphalt, steel, buildings, etc. All these materials represent a carbon sink for the duration of their life cycle. Fossil carbon can be completely replaced by recycled atmospheric carbon. If, in addition to the industrial C-sink materials, considerable quantities of geological C-sinks are created for climate protection, the production of materials from non-fossil carbon and the creation of geological C-sinks would be in direct competition with each other.

Competition for sustainable carbon certainly stimulates the scaling of production technologies, and higher demand will also lead to more innovation and industrialization and, thus, to falling prices. Nevertheless, it is predictable that prices for geological carbon sinks will be much higher than prices for temporary C-sink materials. Factoring in multiple life cycles of industrially used C-sink materials, most of the costs for the provision and transformation of non-fossil carbon are likely covered by the value of the carbon to the various industrial end users. The price of geological carbon sinks, however, would be defined almost exclusively by the long-term climate service (plus some benefits in agriculture and livestock farming). If carbon is removed from industrial cycles for the purpose of long-term (geological) carbon sinks and is subsidized by governments or via high prices paid by carbon removal buyers, competition arises in the carbon sink economy, which drives up the price of non-fossil carbon through increased demand.

Additional costs for geological carbon sinks arise from the incorporation into a C-sink matrix (e.g., soil in the case of biochar or minerals in the case of DACCS), as well as possible land use costs and carbon monitoring. The main cost factor, however, is that the carbon in long-term sinks is not continually utilized and is permanently excluded from the circular carbon economy.

Carbon that is incorporated into materials can be repeatedly recycled, often going through cascades of use (e.g., forest wood that is felled after many years and becomes wooden beams in a roof truss, which later become bookshelves, wine crates or biochar. Or CO2 is synthesized into CH4 to make polyethylene (PE) for sewage pipes, which are later remelted and made into construction film. Or CH4 is pyrolyzed into synthetic biochar and used as nano-carbon in composite materials). If the C-sink materials are finally decomposed biologically (e.g., through the rotting of wood) or chemically (e.g., in aircraft exhausts or waste incineration), the carbon in the material reverts back to CO2 again. CO2 produced in waste incineration, a pyrolysis plant, or a cement factory, can be separated from the exhaust gas at a lower cost and returned to the industrial cycle by synthesizing CH4. If the CO2 is released into the atmosphere, it can be recovered either from there or from the oceans and biomass, where it will be relocated over time. The industrial cycle of non-fossil carbon thus becomes a closed cycle.

The use of biogenic and synthetic carbon in industry constitutes temporary carbon sinks that are constantly renewed as the carbon is continuously recycled from exhaust gases or via the air or seawater. The non-fossil carbon incorporated into materials can be certified and registered as temporary carbon sinks.

Geological C sinks can be certified as C sinks for thousands of years. But as long as not all options for material utilization have been explored and exploited, geological C sinks should be considered a waste of resources compared to C sink materials, because the recovered carbon provides no other benefits beyond the comparable climate service. It's like a pot of gold buried in the garden or a roof beam sunk 20 meters below the foundation of a house instead of being used as a ridge in the trusses to hold up a solar roof.

The intergenerational contract

Temporary carbon sinks must be continually renewed to have the same climate effect as geological carbon sinks. But who can guarantee that a material C-sink, for example, a wooden bridge or the biochar asphalt road, will be replaced after 30 or 50 years when the bridge is renewed and the asphalt replaced by a new wooden building, the planting of a forest, or other material with carbon freshly extracted from the atmosphere? No one can guarantee this so far into the future. Contracts are legally binding for a specified period of time which is usually a maximum of 35 years. If a company goes bankrupt, it is released from responsibility earlier than the specified period.

Considering the legal uncertainty of geological C-sinks, it may seem strange why the obvious solution, i.e., the constant renewal of temporary sinks, is refused simply because there is no legal guarantee that someone will continue the climate-protecting work in the future. Geological C-sinks have no legal guarantee for eternity, either. Who will own the ground in which the C-sink was placed in 50 or 100 or even 1000 years' time? Will the new landowner come to terms with the fact that at some point in the distant past, a previous owner sold the climate service of the C-sink for all eternity and that it was used by an unknown ancestor to compensate for a single flight to Adelaide?

The Earth's climate is a consequence of long-term natural planetary and extraplanetary events and has been increasingly shaped by human activity for the last several centuries. Humanity has always developed in the context of the climate, but as a civilization, it has always stood on the shoulders of the previous generation, from the first tools and fire to the origins of agriculture, from the religious wars and industrialization to the computer age and artificial intelligence. The next generations are in the same but updated historical context. They inherit all of humanity's knowledge, craftsmanship, and technologies, as well as all the problems such as environmental destruction and social injustice. What responsibility does the current generation have for the next generations? Do we have to solve all problems in advance, or can we also pass on some of the responsibility along with the knowledge and technological mastery? May we expect future generations to continue, in their own interest, our work and projects?

The continuation of human civilization and the protection of the planetary nature and climate must be part of an intergenerational contract. If we build a climate protection plan that only works if future generations continue it, we are at least passing on a possible solution instead of leaving scorched earth behind.

In the event that future generations no longer adhere to the intergenerational climate contract and stop recycling carbon, the creation of a geological carbon sink today may at least provide the moral reassurance of having paid off one's own climate debt. But as long as only a few wealthy people can afford to create geological carbon sinks, this will not solve the climate problem or the climate emergency of future generations but will only serve to alleviate the climate guilt of a few. It is much more important to develop robust systems that can be continued in the future and continuously improved. If future generations do not intend to protect the climate, they will have to face the climate that will arise. The responsibility of those living today is not to solve problems for all eternity but to do our part to ensure that future existential problems can be solved in a timely manner with foreseeable solutions.

Ending the extraction of fossil carbon and simultaneously building a carbon recycling industry offers the opportunity to stabilize the global climate through active carbon sinks in consumer and other materials. Of course, the last two generations are primarily to blame for climate change, and it is our duty to do whatever it takes to keep the planet livable for future generations. But our civilization is also passing on to future generations our technological innovations and knowledge of how to limit climate change without sacrificing the quality of life. The interest rate for this inherited knowledge is measured by how well this knowledge is used.

Depending on the production volume and lifecycle of the annual industrial carbon materials, additional geological carbon sinks may be required to stabilize the climate for a certain period of time. However, it is to be expected that the quantities for permanent C-Sinks will be relatively small compared to the global industrial carbon volume since the elimination of fossil carbon and the increased recapturing and reuse of non-fossil carbon will lead to a new planetary equilibrium. Increased reliance on DAC and DOC, and this is the most important argument, will free up land resources for new forests, wetlands, and steppes that do not need to be cultivated with machines, that can store carbon in living biomass, and have far greater value than underground carbon sinks, given the additional ecosystem services they provide.

In the not-too-distant future, the main market for negative emissions will likely shift from a focus on permanent geological (biochar) carbon sinks to the far more ambitious focus on harvesting non-fossil carbon from biomass, DAC, and DOC. Not only will the use of renewable carbon provide enormous economic opportunities distributed across the world, but it will also provide a rapid and economically viable pathway to reduce the need for continued mining of fossil carbon.

Further explanations needed

Previously, the term Direct Air Capture (DAC) has been applied to stripping CO2 from the air and pumping it underground. This article uses DAC to mean only the stripping. Instead of pumping it underground, in this article the CO2 from the air is utilized as a raw material for synthesizing either methane or methanol. This is a radical difference in application that reverses my opinion of DAC. But it depends on the technology for the synthesis. The article variously describes the technology for this conversion as either "emerging" or "today's." There is no citation given for examples of prototypes or implementations. The text of the article gives methane as the end product, whereas Figure 2 shows the product to be methanol. Is the product of this technology methane, methanol, or both? There is not an explanation of the different pathways, so the article is incomplete in that respect.